On work party days, Koji Pingry’s dusty hands place plates of tempura shiso and squash blossoms on the table that his wife, Lizzy Jansen, conjured out of a pile of spare wood. The sizzling tempura complements the percussive cracks of Modelo cans, which visiting volunteers enthusiastically accept. Cucumbers are dressed with cooling hyssop, shishitos are scolded briefly by the flame before being served. A large pitcher of barley tea sweats in the rare Skagit sun. The lunch portion of the work day is a tempting draw for many who come to visit Makanai Farm. “Makanai” means “family meal” in Japanese, so the allure is apt.

Together Pingry and Jansen lease and operate a one-acre farm in Sedro-Woolley. While they grow staples like carrots and kale, their harvest also includes shiso, takanotsume (hawk claw peppers) and mizu-nasu, an eggplant variety from Osaka that is delicious eaten raw. Their vegetables will travel to 100 families in Seattle and many of Puget Sound’s beloved Japanese restaurants, such as Tamari Bar, Kamonegi and Sankai.

A SENSE OF SELF AND PLACE

Pingry is a second-generation Japanese American from north Seattle. He intended to become a teacher, as his mother and many family members had before. However Pingry and Jansen found, rather happily, the intersection of their interests—education, public health and connection to family—culminated in an extended stay in the garden.

“The first person we contacted to learn from and work for was Taki-san. He’s the only Japanese farmer that I knew growing up,” says Pingry. Katsumi Taki is a first-generation farmer who grows Japanese fruits and vegetables in Wapato. “When we decided to farm, it was important to me to pursue a connection to the Japanese American community.”

Pingry and Jansen spent a growing season with Taki, learning how to grow and process Japanese vegetables. When they returned to the Puget Sound, they began working at Skagit River Ranch under the leadership of Eiko Vojkovich, another first-generation Japanese farmer who has been raising certified organic wagyu beef for 25 years.

Pingry says both Vojkovich and Taki helped him grow as a farmer and a person. “It did so much for my own identity development and sense of self and place,” Pingry says. “But it wasn’t until after we got into farming that I started learning more about the legacy of Japanese American farmers in Washington and how far back that goes.”

A LEGACY IN AGRICULTURE

Today, Pingry’s mentors occupy two stalls at the University District Farmers Market, a wan appearance compared to the Japanese agricultural community a century ago.

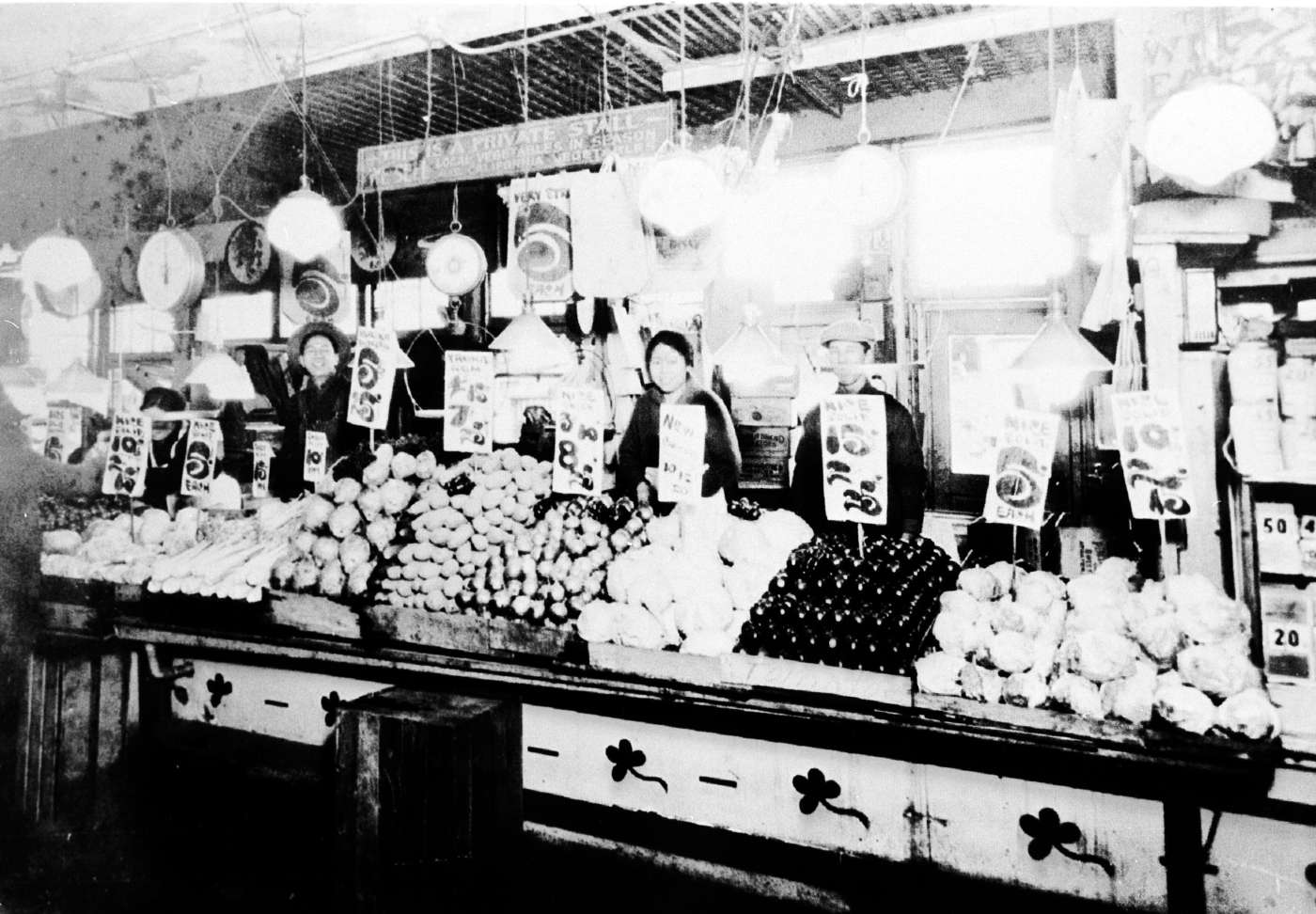

At the onset of World War I, 70% of the stalls at Pike Place Market were occupied by Japanese farmers. Japanese immigrants formed strong agricultural and dairy cooperatives prior to the racist Alien Land Law of 1921, which ultimately barred non-white immigrants from owning land. In 1922, Japanese farms produced 50% of the dairy consumed in Seattle. But by 1925, Japanese farmers produced only 13% of the dairy for Seattle, and farm employment had dropped by 78%. Despite these barriers, Japanese farmers still managed to represent twothirds of the farm stalls at Pike Place Market at the start of World War II.

The incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II dissolved Washington’s Japanese American agricultural communities. Stolen property, vandalism, violence—and the post-war urbanization that paved over their fields, hoop houses, community centers and bath houses in places like modern day Green Lake, Bellevue and South Park—discouraged many Japanese families from returning to farming at all.

The farmers who persevered through the post-war years sowed in a hostile climate. Harvey Funai still pulls sweet corn from the two acres of land in Woodinville his family has farmed since the 1930s. The Funais made an arrangement with a white family to look after their farm during incarceration in exchange for housing and fields replete with crops.

“When they came back, the white people wouldn’t buy anything from the [Japanese] so the local minister, a white male, would take the family’s produce to Pike Place. He dressed up in overalls as a farmer,” says Funai.

The post-incarceration attitude for many Japanese Americans focused on assimilation and reconstruction. Randy Kiyokawa operates Kiyokawa Family Orchard in Mount Hood, Oregon. His family has been farming along the Columbia River since 1911.

“When I was growing up, being Japanese American, it was kind of like the last thing I wanted to be,” says Kiyokawa. “As I’m getting older, it’s more about being a survivor and a family farm and less about being a Japanese American farmer. Nowadays my kids are all proud of that side of their nationality and history.”

Today, young Japanese American farmers are exploring their own cultural history while functioning as a touchstone for the Japanese American community.

Kelly Skillingstead endeavors to honor her own lineage in agriculture at Long Hearing Farm in Rockport. Skillingstead’s mother’s family emigrated from Japan and began farming in the early 1900s. Despite her family’s work on the land, her connection to her cultural past was stifled by incarceration.

“My family basically had all of that stolen from them with incarceration. I’m just crawling my way back into pockets and crevices of what it means to be yonsei [fourth generation]. I think that farming is one of those ways that I can come back into that relationship,” says Skillingstead. “There’s a part of me that really craves that Japanese community to return to, but there’s also the fear and shame of ‘Am I enough to be a part of this?’”

Teresa Shiraishi of Tampopo Farm echoes Skillingstead’s feelings of hesitation and separation.

“I’d like to be part of a Japanese American farm community, but I don’t know if I can say that we are,” she says. “I actually don’t know that many Japanese American farmers currently.”

Shiraishi started Tampopo Farm in 2022 with her partner Matt Rohanna. Together they lease two acres of land in Sequim and grow quintessential Japanese crops, in addition to other staples. Their appearance at farmers markets has drawn Japanese Americans in the area. Their name “Tampopo” means “dandelion” in Japanese.

“Our farm name has brought folks to the market who wouldn’t have come otherwise,” she says. “We’re definitely more connected to a Japanese community than we were before.”

“It did so much for my own identity development and sense of self and place. But it wasn’t until after we got into farming that I started learning more about the legacy of Japanese American farmers in Washington and how far back that goes.”

—Koji Pingry

Koji Pingry looks out at the Makanai fields.

A VISION FOR THE FUTURE

The pull to continue the legacy of agriculture in the region and connect to their own culture is invigorating the current generation of Japanese American farmers.

For Makanai’s 2024 growing season, Pingry and Jansen have hired Michiko Murai, who interned with them in 2023. Murai was initially interested in pursuing her family’s farming culture and history.

“I’ve been very thankful to be introduced to the Japanese farming community through Makanai,” says Murai. “I’ve been so inspired seeing myself in a lot of these people.”

Many of the volunteers and friends that come to Makanai are Japanese Americans and come for community as much as the prospect of a hearty lunch. The future of that community is often on Pingry’s mind. He has a few yuzu and Japanese plum saplings, given by Taki, that he hopes to plant on the farm he owns one day. They won’t flower for several years yet.

“I think about Taki-san on his way out, eventually, who knows how much longer he’ll farm?” Pingry says. “I think about a Japanese American community hub, one that’s really tangible, and about what happens when he no longer shows up at the market every Saturday—and can we continue that legacy? It’s really important to me to keep building out a Japanese American community long-term.”

Learn more about these farms operated by Japanese Americans, or cultivating Asian produce:

Makanai Farm

Pingry and Jansen’s farm in Sedro-Woolley

makanaifarm.com

Tampopo Farm

Shiraishi and Rohanna’s farm in Sequim

tampopo.farm

Mair Farm-Taki

Taki’s farm near Wapato

Read our piece, “Taki-san the Perfectionist”

Sakuma Bros

a fourth-generation berry farm in Burlington

sakumabros.com

Skagit River Ranch

Eiko and George Vojkovich’s ranch in Sedro-Woolley

skagitriverranch.com

Inaba Produce Farms

a third-generation Japanese farm in Wapato that transitioned from Inaba family ownership to Yakama tribal ownership in 2021

Midori Farm

a farm in Quilcene growing certified organic Asian and European produce

midori-farm.com

Long Hearing Farm

a worker’s co-op and certified organic farm in Rockport

longhearingfarm.org