Garden Path Fermentation’s traditional techniques make for avant-garde brews

When you visit Garden Path Fermentation, prepare your palate for something new. Founded in 2016 by Ron Extract and Amber Watts, Garden Path is dedicated to using native yeast, local ingredients and long fermentation times, to adventurous results. The brewery, located in the Port of Skagit industrial park west of Burlington in Skagit County, includes a cozy taproom and bottle shop of their brews, as well as from brewers around the world.

“[Extract’s] been in this industry since before he could legally drink,” says Watts. Extract worked in a pub as a teenager and later started home brewing as a hobby. When he started college, Extract camped out at the campus pub until they gave him a job. He studied brewing at the Siebel Institute of Technology in Chicago, but found that there weren’t many brewing jobs available at that time. Instead, he worked for 10 years for Shelton Brothers importers, building relationships with brewers he admired.

At the same time, Watts was getting her Ph.D. in media studies in Chicago. She met Extract through their mutual interest in craft beer, and the two of them began visiting European breweries and festivals together when Watts had to travel for work.

They moved to Texas when Watts became a professor in Fort Worth, and Extract became a minority partner at Jester King Brewery. They both ended up working at Jester King, but eventually decided they wanted to start their own business, arriving in the Skagit Valley in 2016 to found Garden Path Fermentation.

“We came to Skagit Valley because we thought this was the ideal place to do what we wanted to do,” says Extract.

The climate in the Skagit Valley is reliably temperate, meaning conditions are ideal for fermentation up to 10 months a year. Among other things, the climate makes open-vat fermentation safer, as many undesirable microbes can’t thrive at lower temperatures. Even the few very hot days don’t cause much trouble, since the warehouse has enough thermal mass, which slows the beers heating.

EVERYTHING LOCALLY GROWN

Access to hyper-local ingredients was another big incentive for moving to Skagit Valley. “Everything we source is locally grown,” says Extract. “Ninety-eight percent of it comes within 20 miles of us.”

Garden Path partners with the WSU’s Skagit County extension to get apples from their research orchard. The brewery has access to a vineyard at Carpenter Creek Winery in Mount Vernon, where they tend the vines in exchange for fruit. Some of their hops are sourced from Hop Skagit, and Garden Path also brews with local berries and peaches. “There’s so much awesome fruit here during the summer,” says Extract.

Another big draw was the presence of Skagit Valley Malting, which produced locally grown malted grains. The company closed abruptly a few months ago, so Garden Path is looking for another quality source.

Extract and Watts originally hoped to find a farm where they could build their brewery in order to grow their own ingredients and offer a seed-to-glass experience for customers, but settled for their current space in the Port of Skagit industrial area.

“It’s a great phase one,” says Extract. He hopes phase two will someday be on the farm of their dreams. In the meantime, they have opened a second taproom and bottle shop, The Great Northern Bottle Shop, in downtown Bellingham.

The new shop opened this past summer, and is still evolving. There is a huge bottle selection and an expansive guest tap list in addition to their own beers, a feature which is vitally important to Extract and Watts.

“It’s our ultimate venue, to put everything we love into this shop, and to really go even a step further in showcasing things that influence and inspire us,” says Extract. “It’s really an opportunity to showcase lots of fermented awesomeness.”

Garden Path also hosts “Wine School” and “Beer School”—guided tastings every month to educate curious customers about the different methods they and other breweries use—like open fermentation, spontaneous fermentation and native, wild yeasts.

THE ‘COMFORT FOOD MODEL’

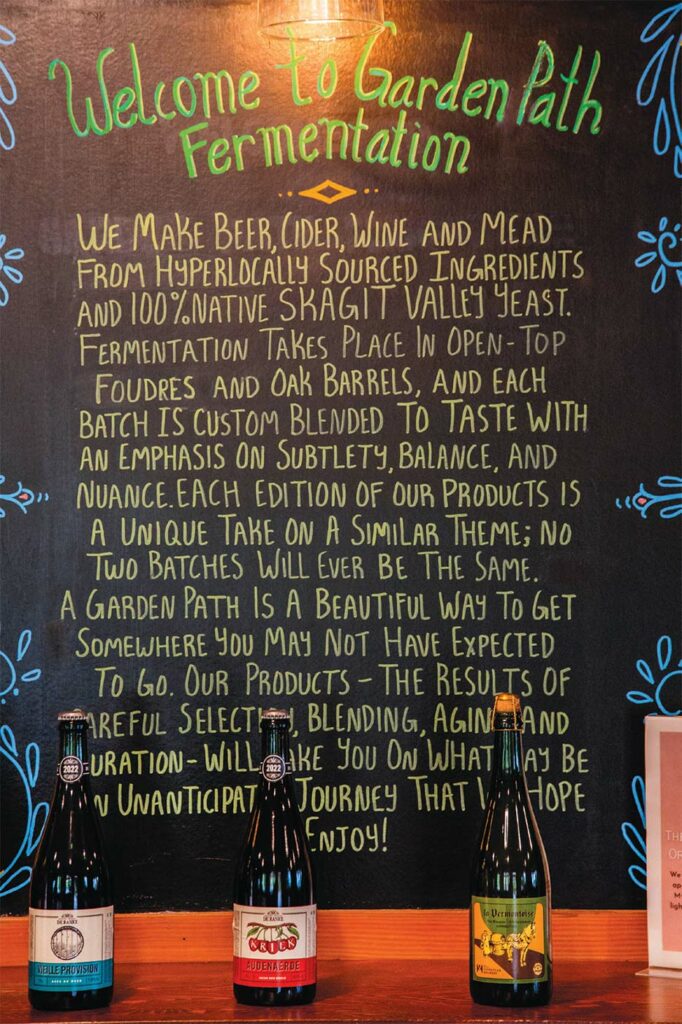

“Brewing tends to be based on what I call the ‘comfort food model,’” says Extract. At most breweries, recipes are precise, so the beer comes out the same each time. At Garden Path, every batch is unique. The wort Garden Path uses (wort is the liquid produced from the mashing process, which contains the sugars that the brewing yeast will ferment into beer) is produced to their own specifications at Chuckanut Brewery, which happens to be just up the road.

Most of their beer is made using open fermentation, where the wort is cooled to its ideal temperature of around 70°F, then put into an open-topped wooden vat called a foudre. Their house culture, which they developed from native yeast, is added and allowed to ferment. Unlike a typical conical fermenter, the foudre allows yeast to move freely and the CO2 vents naturally. The result is a drier brew, as the residual sugars all get eaten, especially with many different kinds of microbes working together. The beer is then aged in oak casks, reused from wineries so very little oak flavor is imparted.

In addition to open fermentation, Garden Path also uses spontaneous fermentation for some brews. In this case, the wort comes back from Chuckanut Brewery boiling hot and gets placed into a coolship, a large, open-topped shallow tank. As the wort cools, it pulls in wild yeast from the air. After 12 to 16 hours, it’s placed in a closed container and allowed to slowly ferment for at least six months. With this method, every batch is inherently unique, and produces extremely complex, intense beers.

Garden Path regularly makes a beer called “The Curious Mix Method,” combining beers made from both open and spontaneous fermentations. Another Garden Path standard, their annual brew “The Wet Hop Ship” is made by filling a coolship with freshly picked hops, then topping them with boiling wort. A foudre is simultaneously filled with warm wort and yeast. Both mixtures are left for a day, before they are combined and left to age.

When finishing their beers, Extract and Watts frequently draw from their casks of aged brews and combine them to achieve different effects, not always knowing where it’s going to end up.

“It’s a winding road that doesn’t always take us where we meant to go,” says Extract. They have two to three times more product aging than they sell in a year, and since they spend six months to a year on every batch, their production is a modest 150 barrels per year. Everything gets naturally conditioned in the can or bottle with young beer or natural honey.

The house culture, used to start almost all of Garden Path’s beers, was made when the brewery was founded, using gathered flowers and leaves to collect native wild yeast. That culture has now made 100 batches of beer, and continues to change and improve.

“That’s part of the reference of our name as well, that our process can sometimes take us down a path we didn’t expect to travel,” he continues. “but to places that are beautiful and worth exploring.”

THE BEST VERSION OF ITSELF

“We rely on [the culture] to tell us what it needs to be the best version of itself,” says Extract. The goal when creating it was to make the saccharomyces microbe dominant, which gives a balanced flavor. While there are many other microbes as part of the house culture, they give complexity without being overpowering. Extract and Watts’s favorite “desert island” beer, representative of this quality for them, is “Taras Boulba” from Brasserie de la Senne in Brussels, which Watts calls “the perfect beer.” It has flavor and complexity, but won’t wear out your taste buds if you drink more than one pint. That balance is what they strive for in many of their beers, like “The Easygoing Drink” or “The Little Horse Around,” which Extract says is “beer that we made to try to be as balanced and approachable as possible.”

“A lot of wild beer is self-described as sour beer—it has hard edges. We don’t consider ourselves a sour beer producer,” says Extract. “What we’re making here are beers that are representative of the Skagit Valley. We’re making Skagitonian ales and maybe someday that’ll be a style, but we’re not trying to make Belgian beer, English beer, German beer or anything else so we don’t use those style designations. We draw inspiration from other traditions and different parts of the world, but then we reinterpret them in ways that we think makes sense with what’s available here.

“That’s part of the reference of our name as well, that our process can sometimes take us down a path we didn’t expect to travel,” he continues. “but to places that are beautiful and worth exploring. We hope to be able to do the same for people who try our products, that it may not fit into the boxes that you expect.”