Tap into the magic of Acme’s bigleaf maple groves

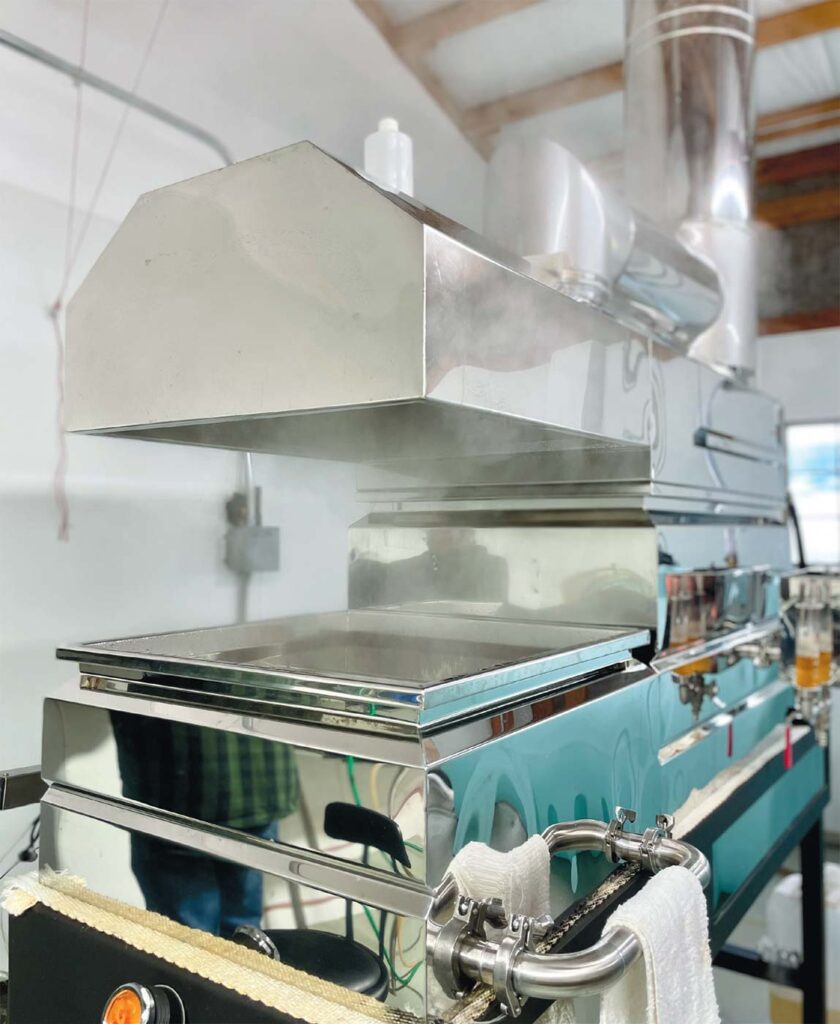

Puffs of steam pour out of an evaporator, through several chrome columns and into the cold winter air as I enter the sugar barn, where Neil McLeod is hunched over a vat of boiling tree sap. This barn is where the magic happens: the team at Neil’s Bigleaf Maple Syrup collects and cooks down this year’s harvest of Washington-grown maple syrup. Yes, you heard that right.

The journey to uncover this local treasure led me to Acme, a small town of only a few hundred residents, tucked in the picturesque countryside of Whatcom County. The McLeod farm spans 200 acres, but it’s a select 10 acres where old-growth maple trees flourish near a gently flowing creek that draws me. These aren’t just maple trees: they are Acer macrophyllum, the magnificent bigleaf maple, a species that was thought unsuitable for syrup production for years. Neil McLeod is proving conventional wisdom wrong, one delicious bottle at a time.

FROM PASTIME TO PRODUCTION

As Neil stirs the bubbling liquid, ensuring it doesn’t foam over, I ask him how he became interested in tapping maple syrup.

“I needed something to add to my coffee,” he admits, a little sheepishly.

It was a humble beginning, born from a simple desire. McLeod explained he originally kept bees for their honey but lost his hives one winter. He had heard about tapping trees for syrup and decided to give it a try, and what began as a hobby quickly blossomed.

McLeod’s wife, Delight McLeod, sits nearby bottling finished syrup as we talk. “He used to come home with jugs of sap and boil it down on a propane burner,” she says.

This initial method yielded around 40–50 bottles yearly, a precious stash shared with friends and family. But it was their son, Devin McLeod, who truly sparked the transformation. Now the business’s frontman, he shared a few bottles with friends working in local restaurants, most notably at Seattle’s renowned Canlis. The response was immediate and enthusiastic.

Devin recalls that the Canlis kitchen asked, “How much can you get?”

Around 2015, the hobby transitioned into a small-batch business. Neil traded his propane burner for a commercial evaporator and invested in a reverse osmosis machine—a crucial piece of equipment that streamlines the sap concentration process by separating water molecules from sugars, vitamins and minerals. The machine leaves less water that needs to be boiled out of the final syrup. The team of three began to get serious about the science of sap collection, refining their techniques, deepening their understanding of the bigleaf maple and obtaining a commercial license.

A bottle of Neil’s Bigleaf Maple Syrup. Since sap flows after a freeze-thaw cycle, the quality of the sap will change with the overall conditions: lighter earlier in the season, darker later on. Image courtesy of Neil’s Bigleaf Maple Syrup

IN THE TREES

Leaving Neil to his work, Devin and I venture into a quintessential dripping day of the Pacific Northwest. Just a week prior, snow blanketed these fields, but now, the temperatures climbed into the low 40s. This is perfect weather to the McLeods’, since a good freeze followed by thawing temperatures translates into one thing: a bountiful sap run.

With its expansive canopy, the bigleaf maple is native to the West Coast, thriving from San Diego to Vancouver Island. For years, the prevailing belief was that these trees weren’t a reasonable choice for sap production, since the sap has a lower sugar content than the sugar maples (Acer saccharum) popular in the Northeast. Unlike the East Coast, where the syrup season hinges on a single freeze-thaw cycle, the West Coast’s more variable climate allows for multiple runs throughout the season. Devin estimates they might get seven or eight runs, starting early in November and continuing through March.

Devin toured me through a grove of maples, where we met with a network of bluish tubing, a complex system that crisscrosses from tree to tree. These tap lines feed into an extractor, eventually leading to large vats awaiting Neil’s ministrations. The trees surrounding us, standing sentinel along the marshy banks of the Nooksack River’s southern tributary, are truly magnificent. Some are old-growth giants, their trunks reaching 3 to 4 feet in diameter. The McLeods, mindful of the trees’ health, typically tap once per foot of circumference, meaning some of these ancient trees might have three or four lines drawing sap.

Tapping maple trees for syrup is a sustainable, noninvasive practice that does not harm the trees if done mindfully. The McLeods are deeply aware of this symbiotic relationship, treating their trees respectfully and ensuring their longevity for future generations.

The transformation from sap to syrup feels alchemical. To produce just one gallon of finished syrup to the optimal 66.5 percent sugar content, Neil must cook down an astonishing 60 to 100 gallons of tree sap. It’s a labor-intensive process that demands patience and a keen understanding of the trees.

Neil’s Bigleaf Maple Syrup has become a coveted ingredient in the kitchens of discerning chefs, including those at Canlis, and a treasured treat for anyone fortunate enough to taste it.

Lucky for me, we returned to the sugar barn for a taste test. Early in a run, the sap produces a lighter syrup full of vanilla notes, perfect to pour over a pile of pancakes. As the run continues, the syrup becomes darker and thicker, tasting like molasses with a rich caramel flavor. Many bakers covet this thicker concoction, including it as an essential ingredient in their pastries.

THE BUSINESS SIDE OF SYRUP

Devin manages their extensive and growing online presence, while Delight produces a newsletter that reaches over 6,000 eager fans. When word goes out that a new batch is ready, it sells out within days. Currently, placing an order online is the only way to secure a bottle, but trust me, come breakfast time, your pancakes never tasted better.

Beyond the alchemy of syrup, Neil McLeod is deeply fascinated with the bigleaf maple itself. He’s passionate about promoting its cultivation and encouraging others to enter the syrup-making business.

“More people making syrup is good for the environment,” he says. Maple trees, he explains, are an investment in the future. They sequester carbon from the atmosphere and aid in restoring soil and creek beds, effectively reducing erosion.

With this in mind, their commitment to their trees goes beyond the syrup they harvest. The next chapter for the McLeods looks to the future with sustainable farming practices and reforestation programs. Hanging out in the sugar barn for an afternoon showed me that Neil’s Bigleaf Maple Syrup is more than just a sweetener, in this barn there is a unique story, as well as the quintessential terroir of the Pacific Northwest.

Syrup bottles in hand, I leave the steaming, sugar-smelling barn looking at bigleaf maples with a new appreciation, and a hunger for something sweet.