Pacific Harvest teaches foraging, and how to be a good steward

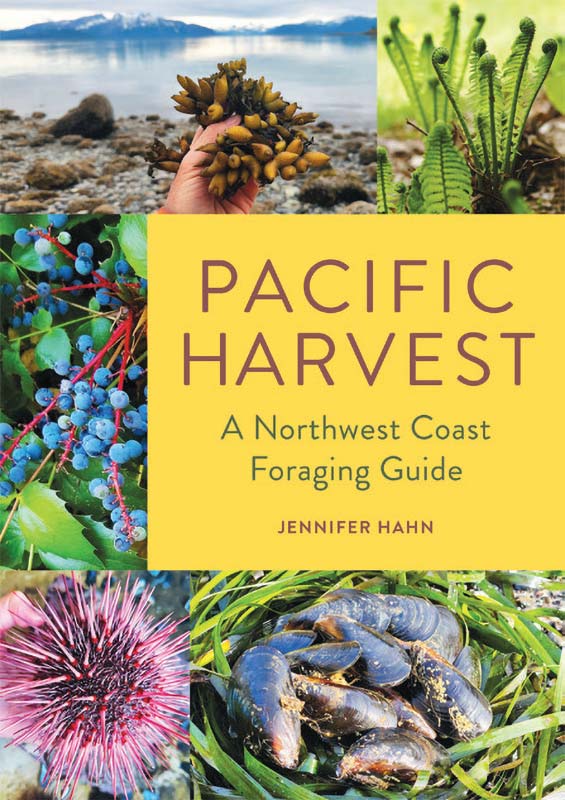

Pacific Harvest: A Northwest Coast Foraging Guide

by Jennifer Hahn

Skipstone, Mountaineers Books, 2025

You can’t help but be magnetically drawn to Jennifer Hahn when she starts talking about foraging. She will animatedly hold up a segment of bull kelp, or point to a patch of purslane, explaining its properties and why it likes to grow where it does. She eagerly doles out samples, and will absolutely share the recipe. She holds vast plant history and cultural context in her brain, and easily shares it with anyone eager to learn.

Like many compelling teachers, Hahn is a perpetual student—listening and learning from the wild teachers of land and sea, First Nations and tribal elders, scientists and chefs alike.

I met Hahn many years ago, shortly before her first foraging book, Pacific Feast, was released. I was a student at Western Washington University, taking an Ethnobotany course at Fairhaven College. Hahn was a guest lecturer, and was such a resounding success that the class was invited at the end of term to visit her Bellingham home and do a little foray around her property to see what spring had to offer. We foraged for nettles, maple blossoms, wood sorrel and evergreen tips, and made quite the little feast, sitting outside on the ground and asking her questions about foraging and her adventures as a guide and solo kayaker. I still regularly refer to my battered copy of Pacific Feast for inspiration.

Needless to say, Hahn made an impact.

So when Pacific Harvest was announced, it came as no surprise that it was even more thoughtful, comprehensive and beautiful (Hello, full color photos throughout!) than her first guide. Hahn’s deep love of this region is apparent, and the same goes for all the elders and educators who also lent their words and expertise. Like many dedicated naturalists, Hahn has been profoundly impacted by her foraging expeditions, as they have shown her how interconnected we are with our ecosystems, and the continuum of humans and animals finding food.

“I could imagine a long feast table spanning from Yakutat Bay in Southeast Alaska right past my wavesloshed boots to Point Conception, California,” Hahn writes in her introduction. “ I could see it rising from the Pacific Ocean to the crest of the Cascade Mountains and over the lip. Since the great Ice Age, that three-thousand-mile-long table is where Northwest coast Indigenous peoples traversed rainforests, clamsquirting beaches, wildflower meadows, muskegs and river estuaries to gather all the food, medicine and supplies they needed to live.”

The book is broken up into two main parts. The first, “Guide to Wild Morsels,” is broken down into sections about wild and weedy greens, berries and roses, trees and ferns, mushrooms, seaweeds and beach vegetables, and shellfish.

Each food entry has some of the expected information: the species’s common names and taxonomy, locations, a written description and a photo. What sets the guide apart in my mind is the consideration Hahn and her collaborators have taken to share more than just the information you need to find and harvest the plant—you need to be able to give back, and consider the future for that plant, animal or habitat.

To that end, Hahn has included sustainable harvest tips, culinary advice and my two favorite sections—first, “Who Eats and Shelters Here?” to help you keep in mind the other creatures that depend on these wild foods for sustenance and shelter, so you only take what you need. As Hahn writes, “Humans have alternative food sources, but other animals don’t.” The other section is “Foraging for the Future,” which provides scientific and field updates, encouraging you to always consider the health and longevity of these species.

Throughout the book are educational sidebars with clever names like “Clam-ping Down on Poachers” about geoduck poaching in the San Juan Islands, or “What’s up with our massive maples?”—about the phenomenon called “bigleaf maple decline.” There are also profiles of educators, elders and knowledge keepers in the traditional food movement—many of them familiar faces, like Valerie Segrest and Jared Qwustenuxun Williams.

The second part, “Recipes for Foraged Foods” will help you use every bit of those foods you so lovingly foraged—Salal Berry Scones? Yes, please. Dandelion-Daikon Kimchi? Absolutely. Uni Carbonara?! Say less, I’m already hungry.

The core principle of Pacific Harvest is stewardship of these species and ecosystems, and Hahn gives us the helpful mnemonic “STEWARDSHIP” to guide us in sustainable foraging practices:

SUSTAIN NATIVE WILD POPULATIONS

- Tread lightly

- Educate yourself

- Waste nothing

- Assume the attitude of a caretaker

- Regulations, restoration and reciprocity

- Don’t harvest what you can’t identify

- Share with wildlife

- Harvest from healthy populations and unpolluted sites

- Indigenous people’s traditional harvest sites deserve respect

- Pause and offer gratitude for your harvest

Hahn encourages us all to keep these in mind as we forage wild foods, especially in this time of climate upheaval. Many plants and animals are being profoundly affected by habitat loss, overharvesting and pollution, and it’s our job to protect and restore these species, especially if we plan to harvest them. Hahn recounts that Segrest told her students, “You have no business foraging if you don’t help restore.”

Pacific Harvest is a foraging guide, a cookbook and an invitation to reconnect with the lands and waters we live on, and the species that nourish us. As Hahn demonstrates, there is abundance all around if you take the time to pay attention.

“When you’re out foraging, engage all your senses,” writes Hahn. “Notice the aromas, the birdsong, the hush of the water or wind as it travels through the landscape around you. Take your kids with you, or someone else’s kids. Help the sprouts grow deep and wild roots.”

I can guarantee that my copy of Pacific Harvest will be just as dog-eared and battered as her first book.

VINE MAPLE

Acer circinatum

FAMILY: Aceraceae (Maple)

STATUS: Native

OTHER NAMES: Tree of the devil, wood of the devil (Scottish botanist David Douglas logged in his journals that the vine maple “is called by the voyageurs Bois de diable from the obstruction it gives them in passing through the woods.”)

This vine-like tree or large shrub sprouts multiple trunks. Up to 20 feet in length, they may sprawl across a shaded forest floor or rise in ethereal arches overhead. In sunny, open sites the vine maple appears more upright and bushier. The scientific name circinatum means “circular” and refers to the rounded 3- to 4 ½-inch-wide leaves with palmate veins and toothed edges. In spring, I’ve noticed the buds open like tiny cocktail umbrellas. Greenish-white flowers grow in clusters of 3 to 6. The winged seeds spread horizontally, not in a V-shape, and gain a rose tinge. Autumn leaves range from yellow to orange to red. British Columbia to Northern California in damp, shady woods, often along streams.

HARVEST GUIDE

What: Leaves

When: Autumn

The tradition in Osaka, Japan, is to collect yellow leaves after they’ve fallen. I like that thinking. It feels more like the tree decides when to “leave off” and share its gifts.

CULINARY TIPS

Tempura the whole, yellow autumn leaves and serve atop your favorite ice cream for a gorgeous, crispy-crunchy autumnal garnish. (Recipe to follow)

WHO EATS AND SHELTERS HERE?

Black-tailed deer munch the leaves. During fall migration varied thrush overturn the fallen leaves with a deft flip of their bills and hunt for insects. Douglas squirrels slice open the tough seed capsule on the samaras (winged, helicopter-like seeds).

Songbirds such as chickadees, nuthatches and pine siskins hunt for insects and hide in arching vine maples. Several species of squirrels and woodpeckers travel the trunks looking for insects and seeds.

Guide entry and recipe excerpted from Pacific Harvest: A Northwest Coast Foraging Guide by Jennifer Hahn. Used with permission from Mountaineers Books. This recipe has been adapted for use in Edible Seattle.